Outwardly identical, yet distinct

All placozoans are superficially identical. But comparative genomic data reported by an LMU team reveals the presence of different genera. This is the first time that a new animal genus has been defined solely by genomics.

01.08.2018 at 00:00

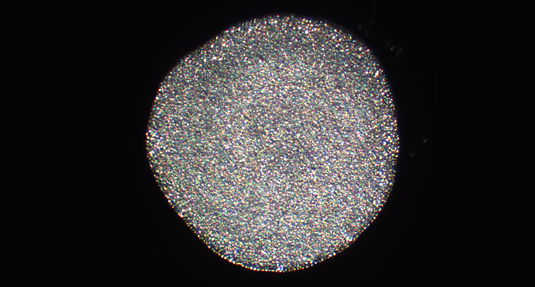

Hoilungia hongkongensis. Source: Hans-Jürgen Osigus, Stiftung Tierärztliche Hochschule Hannover

Up until quite recently, the animal phylum Placozoa enjoyed a unique position in animal systematics. It was the only phylum to which only a single species had ever been assigned: Trichoplax adhaerens. Now, however, at team led by Professor Gert Wörheide of LMU‘s Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and GeoBio-Center has discovered that placozoan specimens collected from coastal waters off Hong Kong clearly differ from T. adhaerens in their genetic make-up. Indeed, the differences between the two are so striking that the Hong Kong population not only represents a new species but also has been assigned to a new genus – even though the two genera are morphologically indistinguishable. The definition of a new species and genus solely on the basis of comparative genomic data constitutes a new departure in the systematic classification of animals. The findings appear in PLOS Biology.

Placozoa are among the simplest known multicellular animals, lacking both muscles and nerve cells. They are only a few millimeters long and their cells are organized into two flat layers. They have been found in tropical and subtropical waters around the world. But, regardless of locality of origin, all placozoans have the same gross morphology and same basic cellular architecture. Since conventional approaches to the definition and differentiation of animal species rely on differences in overall body plans and detailed morphology, all placozoan specimens so far collected have been attributed to the species T. adhaerens, which was first described in 1883. “However, genetic data based on short DNA signature sequences that serve to distinguish species from one another had already suggested that placozoans exhibit a great deal of genetic diversity. And that in turn indicates that the phylum actually includes many different species,” says Wörheide.

For this reason, he and his colleagues decided to sequence the genome of a placozoan line derived from specimens collected in Hong Kong. Their signature sequences indicated that this line was distantly related to T. adhaerens, whose genome was published in 2008. “Based on comparative genomic analysis, we then developed a novel method for the description of a new species based exclusively on genomic data,” says Michael Eitel, first author of the new study. The researchers refer to this approach as ‘taxogenomics’, which takes into account factors such as structural differences between chromosomes, differences in the total number of genes, and sequence differences between selected protein-coding genes.

The genetic and genomic data for the placozoans from Hong Kong revealed such large differences between them and T. adhaerens that they were ultimately assigned not only to a new species, but to a new genus, which represents a higher rank in the hierarchy of biological taxonomy. “This is a completely new departure. It is the first time that a new genus has been erected purely on the basis of genomic data,” Wörheide explains. The new species bears the name Hoilungia hongkongensis. This translates as ‘Hong Kong Sea Dragon’ – which refers to the fact that, just like the Dragon King in Chinese mythology, placozoans can readily alter their shapes.

The authors of the new study believe that the placozoans may have undergone a very peculiar mode of evolution, in which speciation has occurred exclusively at the genetic level without notable morphological diversification. “We have some indications that point to the operation of negative selection, so it is possible that the development of morphological novelties may be repressed. But we are still very much at the beginning of the search for an explanation of this unique evolutionary trajectory,” says Eitel.

The authors also suggest that the taxogenomic approach could also be used for detailed studies of the process of speciation in other animal phyla. This holds in particular for animal groups that consist of minuscule individuals, such as nematodes and mites, in which it is often difficult to discriminate between species by optical inspection alone.